No most probably not but with the right setup it can make it a quicker process. People often see code reviews only as a way to enforce coding standards in an application. While this is important, for me its more about communicating changes to each other so that information isn’t siloed. That is why its perfectly reasonable for a junior developer to code review a seniors changes.

What NDepends tries to solve for is an automatic way to evaluate code submitted against the team coding standards. It automates best practices by running analysis on your solution to determine how good your change is.

To test it out, I installed the visual studio plugin and ran it against a solution I’m actively developing against. I must make it clear that I did no configuration with NDepend at all. In a real scenario, its settings should be tweaked by your team based on what is important to you.

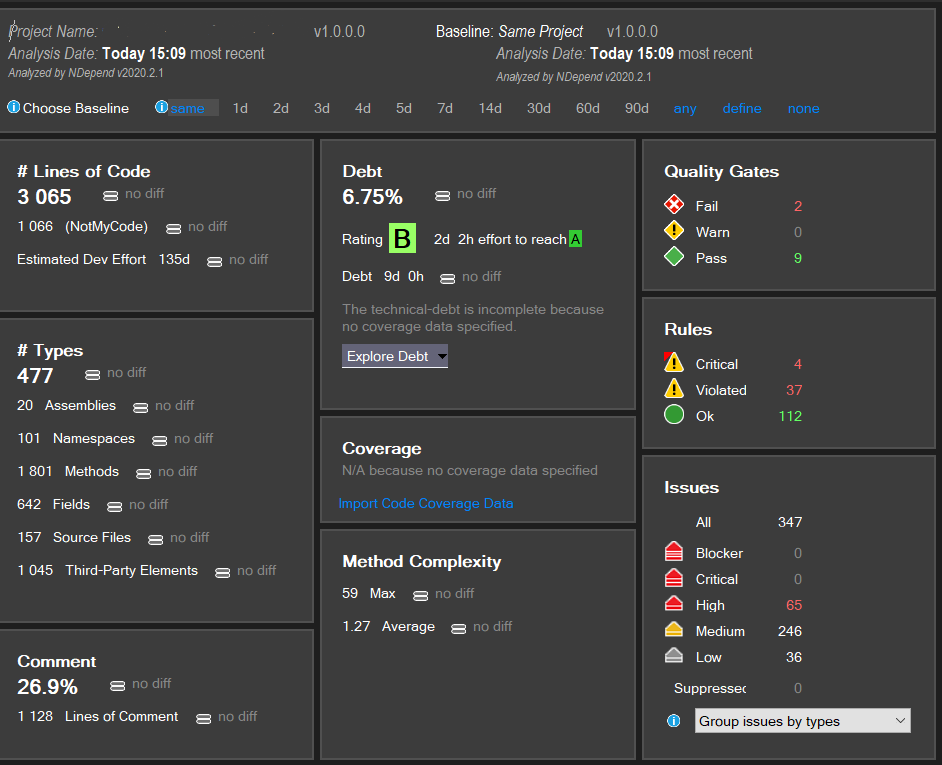

This is the report that was generated on my project.

Quite a lot of information already including 4 critical rules broken.

Before I go through the broken rules, there is an important feature I should mention. You can set a baseline for the analysis. Your report can then show you what has changed based on your rules. A meaningful baseline might be for example the last production release. By doing this you can only worry about if your code is getting better or worse instead of trying to address years of bad code ;)

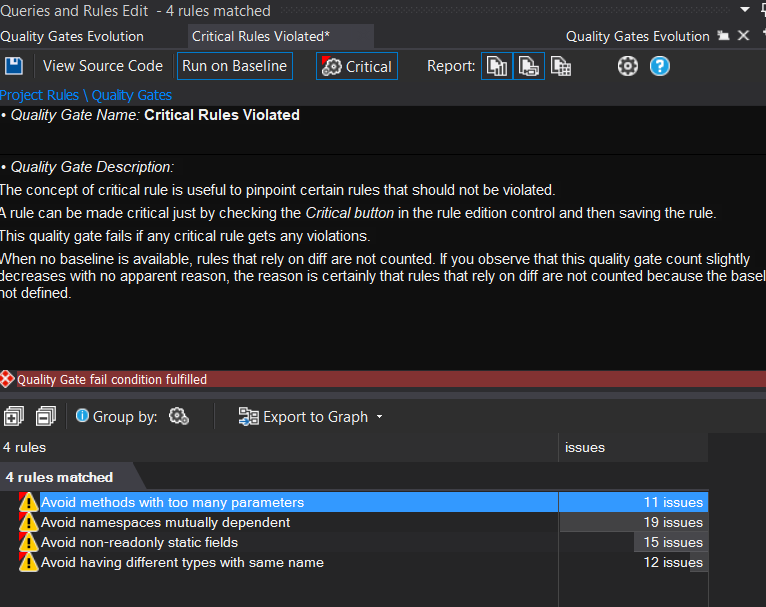

And now digging deeper into the critical rules broken.

For each one you can view the source for all cases that have broken it and a basic description of why NDepends thinks its a problem.

Now let me go through each one to see how useful they actually are in our case.

Avoid methods with too many parameters

This rule picks up any method or constructor with 7 or more parameters. Its pretty reasonable thing to check for and something that often would come up in a code review. Generally it can be a little painful to work with these types but I think they can be mitigated often with the use of things like dependency injection. You could still have the argument that a class that injects 7 or more dependencies is most probably not following the single responsibility principle.

In my case I have a valid reason. Our project has null checks enabled and so our DTOs pass the values for all properties through the constructor. We generally only create the DTO with Deserialization which negates the issue with many parameters.

A reasonable thing to do in this case might be to configure NDepend to ignore my DTO library as part of its checks.

Avoid non-readonly static fields

This was a good insight. We had a couple of static fields that were used like a const across instances. By not making them readonly, any instance could create a new one. Of course its still dangerous if our readonly static field is mutable but this was a good insight.

Avoid having different types with the same name

The rule flagged cases where we have classes with the same name. So if two projects have a Request class, it can be confusing to a development team on which Request object you are referencing.

I think there are exceptions to this rule as well. In our application, each project defined its own ServiceExtensions class which is the common way to define dependencies for that library. The main startup.cs class can just call a method from this class to register everything it needs. Personally I don’t see an issue with them all called ServiceExtensions because it is an understood pattern in our team when setting up dependencies.

Avoid namespaces mutually dependent

To be honest I’m not sure I really understand this rule. The explanation is that its avoiding a pattern that is associated with spaghetti code. To be clear: I don’t want someone to accuse my code of being spaghetti! The rule looks for a cyclical dependency between a lower and a higher type. One thing that was flagged was something like this:

namespace ABC.People.Services

{

public interface IPersonService

{

Person Get();

}

}

namespace ABC.People

{

public class Person

{

}

}

To be honest its not something that I think is a big deal but you could argue that its a symptom of badly organized code. The Person class in this case was just stuck in the root without moving it into its own folder.

Summary

These broken rules were obviously just a very simple test with the default rules. The important thing is that when configured correctly, you can codify what good code looks like. If you are willing to spend the time configuring the rules then your code reviews move from checking for these things to communicating the intention of the code. In my opinion this is time well spent.